Plague in London

During the ravages of

Covid, many of the world’s great cities suffered an existential crisis and experts

were quick to proclaim the death of city living. Yet already in 2022 cities are

back, no more so than London. West End footfall has already exceeded pre-Covid

figures and theatres and restaurants are enjoying a resurgence in popularity.

Estate agents report large numbers of people who fled London now wanting to

return. A good time, I thought, to take a look at that other cataclysmic event

which should have ‘done for’ London… but didn’t.

Bubonic plague was present in this country throughout the 14th -17th centuries with at least 12 serious outbreaks and many more minor ones between 1094 and 1665. The 14th century brought a particularly virulent outbreak of the disease. Rumours emerged in 1346 of a disease that had broken out in Asia, killing thousands of people. They called it the ‘Great Pestilence’, we now call it the Black Death, a name originally coined due to the way in which corpses became badly discoloured after death. It finally reached London via the wool trade at the end of 1348. Over the next 18 months, it killed around half the population of England and an even higher percentage of Londoners – 30,000 lives. Graveyards filled up and two emergency cemeteries had to be opened. Unlike in later outbreaks, there was no mass flight from plague at this time as towns and cities outside London were equally affected.

|

| Rattus rattus |

There were six further outbreaks in the 14th century and, though the population took 150 years to recover, by 1660 it stood at around half a million, mainly accounted for by an influx of migrants from poorer rural areas of the country. But then in the 17th century London suffered its greatest onslaught from the plague. It killed over 30,000 Londoners in 1603 and 40,000 in 1625. But the worst (and last) outbreak happened in 1665 and killed over 80,000 citizens.

|

| Distribution of plague cases |

A disease of the black rat (Rattus rattus), the ‘Great Plague’, as it became known, was transmitted between rats by fleas and infected humans by means of flea bites, an open wound making contact with plague-infected material, or infected breath. It was not, as was thought at the time, attributable to noxious vapours, divine retribution or misalignment of the planets. The disease incubated for 2-6 days, then flu-like symptoms developed plus discomfort in the groin and under the arms. Then buboes appeared and a fever. Death followed in 2-3 days, later within just hours.

It started in St Giles, a notorious slum. Other plague-ridden

settlements included Holborn, Shoreditch, Finsbury, Whitechapel and Southwark –

all squalid areas outside the City. It started slowly until June brought a

heatwave and numbers infected rocketed.

|

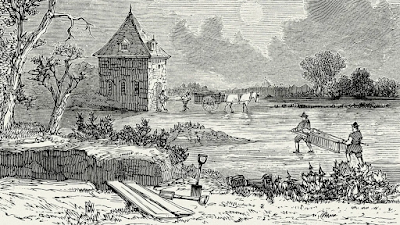

Pest-house, Finsbury Fields |

Some people, naturally, decided to flee. Many took to living on boats moored mid-river, but those with greater means left the city altogether. Their number included doctors, clergymen, lawyers… and the King and his entire court. The monarch returned in December of 1665 but Parliament only reconvened the following spring.

For those with nowhere to go, London was transformed into a place

of ‘dismal solitude’. According to one eye witness: “every day looks with

the face of the sabbath-day… shops shut, people rare, very few places to walk

about insomuch that the grass begins to spring up in some places… no rattling

coaches, no prancing horses, no calling customers, no offering wares, no London

cries…”

|

| Plague broadsheet by John Dunstall |

|

Plague handbell |

Despite the various measures that people took to prevent being infected - carrying branches of rue and wormwood, sucking lozenges, drinking tinctures, wearing amulets and pomanders and smoking tobacco (children too!) to protect themselves from infection, the disease marched on. Such was its terrifying impact, Thomas Vincent wrote: “[death rode] triumphantly on his pale horse through our streets and breaks into every house almost where any inhabitants are to be found”.

The diarist Samuel Pepys, who stayed in London throughout the epidemic, wrote in early September: “I have stayed in the City till above 7,000 died in one week, and of them about 6,000 of the plague, and little noise heard day or night but the tolling of bells".

|

"Bring out your dead!" |

Large communal graves lined with quicklime were dug outside the city as the churchyards were full up. There was a constant backlog of corpses waiting to be buried. Statistics on deaths are left to us in the form of what were known as Bills of Mortality, drawn up by clerks of city’s 130 parishes. These make grim reading, not just for the information on plague fatalities but as an insight into the myriad other dreadful illnesses – now eminently treatable – that people could lose their lives to.

|

Bill of Mortality 1664 |

|

Bill of Mortality 1665 |

Yet despite the ravages of the plague, London continued to thrive and the population just 30 years later had reached an incredible half a million. Despite the inevitable downsides of poverty, overcrowding and disease, London remained – and remains – a draw for people looking for opportunities of all kinds.

References:

The Times History of London ed. Hugh Clout

Article: Social Capital: Covid has changed London for the better

Richard Florida (Spectator 2 April 2022)

The Book of London ed. Michael Leapman (1989)

London: The Illustrated History Cathy Ross & John Clark (2008)

London Through the Ages Harold Bagus (1982)

London: a Social History Roy Porter (1994)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home