The George Inn

These

days still a bustling social hub and a great place to eat close to London

Bridge, the George Inn is London’s only remaining galleried coaching inn. Despite

the mutilation inflicted on the building by the Victorians (in the name of

progress, naturally), its original character is still evident both inside and

out and it remains a popular watering-hole for local workers and visitors alike.

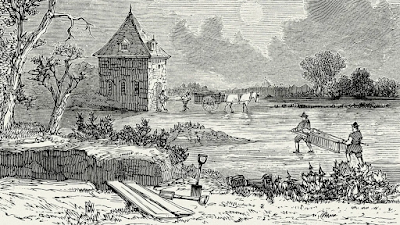

Borough High St was once lined with coaching inns, catering to the needs of the large numbers of people travelling into the City over London Bridge (it was the only means of crossing the river right up until 1750) as well as those heading south out of London, particularly pilgrims en route to Canterbury. Most of these inns have long since disappeared but evidence of their location survives in the names of alleyways off the High St, e.g. King’s Head Yard, White Hart Yard, Talbot (Tabard)Yard etc.

The earliest known reference to a Saint George & Dragon Inn

is on a map dated 1542 (its name was only shortened in Cromwellian times). We

know that it was already well established during the reign of Henry VIII, and that

the first known innkeeper was Nicholas Marten in 1558. The George also features

in John Stow’s Survey of London of 1598, a time when Southwark was best known

for its brothels and bear-baiting: “towards London bridge […] be many fair

inns, for receipt of travellers”.

which raged throughout Southwark for two whole days before being brought under control. More than 500 houses were destroyed, along with the George lnn and all its outbuildings. It re-opened in 1677 and today’s building, with its long coaching yard, original balustraded open galleries and small-paned windows, dates from that time.

During the 18th century, horses, carriers’ carts and coaches used the inn as a London terminus. The schedule included four coaches each day bound for Maidstone, two per day for Canterbury and Dover, and one every day to Brighton and Hastings.

In 1825, the George was described as “a good commercial inn, whence wagons depart laden with the merchandise of the metropolis, in return for which they bring back from […] Kent that staple article of the county, the hop, to which we are indebted for the good quality of the London Porter”. At its peak the inn entertained 80 coaches a week.

By 1844, the inn was being run by Frances Scholefield, a

widow. In 1849, with the arrival of the railway starting to eat into demand for

coaching accommodation, Scholefield leased some of the premises to the trustees

of Guy’s Hospital, which was on the eastern boundary of the original inn, so

that they could enlarge the hospital grounds.

For a while, the inn continued to be busy. On census night

in 1851, 15 people were staying in the George, including a sailor, an architect,

a commercial traveller, two waggoners and a customs house clerk, as well as the

resident staff.

But as the railways took over the transportation of goods

once brought by coach, demand for accommodation declined sharply and rooms that

had once been bedrooms began to be used for sundry other purposes, including by

commercial travellers as a place to show their goods.

|

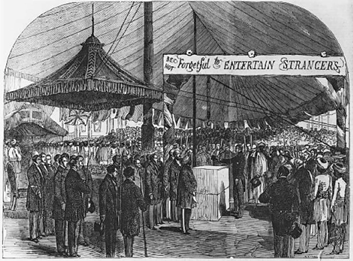

| The George in 1889 |

Fortunately, despite the destruction wrought externally, the

interior of the pub retains much of its original character. What is today the

Parliament Bar was once the tap room of the pub, a dark space with panelling

where, according to Bertram Matz’ book of 1918: “[there] gathered in

the old days the coachmen; the Tony Wellers of his day and before, with their

long clay pipes and tankards of beer, met to discuss the events of the day and

the road, whilst the ostlers saw to the watering and care of their horses

further down the yard.”

The Middle Bar today was once the Coffee Room, known to have been frequented by Charles Dickens (it’s mentioned by name in ‘Little Dorrit’). He was evidently well-acquainted with many of the inns of this area, describing them as: “Great, rambling queer old places[…], with galleries, and passages, and staircases, wide enough and antiquated enough to furnish materials for a hundred ghost stories”.

.jpg) |

| Former Coffee Room |

The restaurant upstairs in the galleried part of the building is where the guest bedrooms used to be.

Now under the guardianship of the National Trust (it was gifted by the LNER in 1937) the George is Grade I-listed due to its status as London’s last galleried coaching inn, and as a location with proven literary associations.

References:

Taverns

in Town by Michael

Roulstone (1973)

The Times

History of London by

Hugh Clout (2004)

Coffee room

photo from George Percy Jacomb-Hood’s "The George Inn, Southwark":

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50284331

The

George Inn Southwark: a survivor of the old coaching days by Bertram Matz: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_George_Inn,_Southwark

,_Piccadilly_Circus,_London_(2).jpg)