The London Hospital

Emerging from the tube onto Whitechapel Road, it’s hard to

miss the giant hoarding that faces you across from the market, almost (but not

quite!) obscuring the imposing structure that is/was the Royal London Hospital.

Known to many through its association with its most famous ‘inmate’, the Elephant

Man, others will be familiar with it from frequent references to ‘The London’

(as it is still known locally) in the BBC’s ‘Call the Midwife’ series.

The London Hospital started life in 1740 as

the London Infirmary. With a total of just 39 beds, it was located in a house

in Moorfields, leased by the surgeon John Harrison to provide care for the sick

poor of the ‘merchant seamen and manufacturing classes’. It was, and would long

continue to be, funded by voluntary contributions. The Infirmary had no water

flushing system so waste was carried in buckets at night to be dumped in the

hospital cesspool or the street!

In 1741, the facility moved to Prescot St

in Whitechapel, changing its name in 1748 to The London Hospital. Three years

later, in 1751, the decision was taken to build a new hospital and land was

bought on Whitechapel Road (the current site) for this purpose. The new

hospital, built at a cost of £18,000, had 350 beds and resembled a stately

home. Standing amidst the green fields and farms of rural Whitechapel, its main

disadvantage was a huge, festering rubbish dump to one side, known as ‘The

Mount’ (the name is preserved in nearby Mount Street and East Mount Terrace),

but it did at least have flushing water! Patients were eventually admitted in

1757.

|

| Royal London Hospital facade overlooking Whitechapel Road |

In 1785, the London Hospital Medical

College was founded, the first medical school in England. Famous names

associated with the institution include James Parkinson (who identified

Parkinson’s disease in 1817), John Langdon-Down (who identified Down’s syndrome

in 1859) and Thomas Barnado, who arrived in London from Dublin in 1866 to study

medicine but soon directed his attention to helping the city’s homeless children.

In that same year he established a shelter off nearby Ben Jonson Road, before

going on to open his first home in Stepney Causeway. For the next 35 years

Barnado devoted his life to East London’s children and, though he never

actually finished his medical studies, was accorded the title of doctor in

recognition of his philanthropic work.

|

| Cotton Ward 1910 |

Whereas in the 18th century, a

large part of the hospital’s work was in treating diseases such as smallpox,

typhoid and cholera, in the 19th it specialised in dealing with accident

cases from the docks. In 1840 the hospital needed to be extended, including the

addition of a Jewish ward with its own kosher kitchens and cooks. In 1847, the

first ever operation to be performed under anaesthetic took place here. By

1876, the London was treating around 30,000 patients annually with 650 in wards

at any one time.

In 1886, two more wings were added, making The

London the largest voluntary hospital in the country. Such a vast, and growing,

medical facility, required a steady stream of funds. By the 1890s, it required

public subscriptions and donations amounting to £30,000 in order to function.

It is doubtful that the hospital would have survived to the present day (it

only stopped being a voluntary hospital in 1948) if it hadn’t been for the work

of Lord Knutsford, the hospital’s chairman from 1896-1931, who is credited with

having raised a massive £5 million in funding.

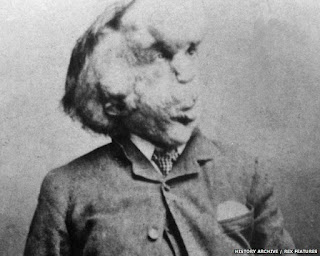

As far as patients are concerned, probably

the most famous name associated with The London is that of Joseph Merrick, otherwise

known as the Elephant Man. Merrick had been exhibited as a freak in a former

shop at what is now 259 Whitechapel Road, directly opposite the hospital. When

he was found by the eminent surgeon Frederick Treves, the latter took him under

the protection of the hospital, giving him his own room in the basement until

his death 5 years later in 1890. A replica of Merrick’s deformed skeleton is in

the hospital’s museum, located in the crypt of the former hospital church of St

Augustine and St Philip in nearby Newark Street. The actual skeleton is

preserved in the medical college’s specimen collection and is only accessible

by researchers with an interest in Proteus syndrome (from which Merrick is

thought to have suffered).

Another important

connection is that of the nurse Edith Cavell, who trained at the London

Hospital from 1896-1901. The hospital opened its nursing school, one of the

country’s first such facilities, in 1873. During WW1, Cavell went to Belgium to

tend war casualties and became involved in underground resistance activities.

She was eventually betrayed and was charged with espionage and executed by a

German firing-squad in 1915 for her part in helping allied soldiers to escape

into neutral Netherlands – this despite appeals by none other than the

President of the United States, the King of Spain and the Pope.

Another important

connection is that of the nurse Edith Cavell, who trained at the London

Hospital from 1896-1901. The hospital opened its nursing school, one of the

country’s first such facilities, in 1873. During WW1, Cavell went to Belgium to

tend war casualties and became involved in underground resistance activities.

She was eventually betrayed and was charged with espionage and executed by a

German firing-squad in 1915 for her part in helping allied soldiers to escape

into neutral Netherlands – this despite appeals by none other than the

President of the United States, the King of Spain and the Pope.

During WW2 the London Hospital, like the

rest of the East End, was heavily bombed. A total of 137 bombs fell within its

grounds, including a V1 rocket in 1944 which killed two patients. After the

war, in 1948, the hospital joined the newly-created NHS, ending over 200 years

of being voluntary-funded. In 1990, it was renamed the Royal London Hospital

and in 1995 it merged with St Bart’s and the London Chest Hospital. Since 2013,

the hospital has occupied new premises behind the old structure.

Much of the original hospital has been/is being demolished, but the

Victorian façade is to be restored and embellished as part of a scheme to

re-purpose parts of the old building to create a new town hall and civic centre

(including a library and café) for Tower Hamlets. Many of the hospital’s

original features will be preserved, e.g. lightwells which once served the

hospital’s operating theatres will now illuminate office spaces. The new

complex is due to open in 2022.

|

| Lightwell incorporated into new building |

In line with its motto: “Humani nihil a

me alienum puto” (I am human; therefore any human is my concern), the Royal

London continues to care for its East End patients – many with the complex

needs associated with poverty - just as it did their predecessors back in 1740.

References:

Hospitals of

London Chambers & Higgins (2014)

The London

Encyclopedia ed. Ben Weinreb (2008)

The East End

Nobody Knows Andrew Davies (1990)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home