The Limehouse Seamen’s Mission

First glimpsed on a walk around Limehouse some years ago, I

had the opportunity during this year’s Open House event to venture inside this

iconic building at 747 Commercial Road. With its tall windows, long upright

mullions, and stone turrets, the structure looks for all the world like a

cathedral. It is only when you look at the inscription that you realise what

its function was, and how significant a role it played in London’s maritime

history.

Many of those working

on the ships or in the docks were what were known as ‘lascars’, a term which

was coined to describe any non-white sailor and included men from Africa and

the Middle-East as well as Asia. These were hired in large numbers and were the

majority on many ships. Captains often preferred ‘coloured seamen’ because they

could pay them less, were more comfortable in hotter climates and, if they were

Muslim, did not drink alcohol.

Limehouse quickly

grew into a diverse neighbourhood. The book ‘Living London’, published in 1902,

provides a vivid snapshot of how the area must have looked: “It is in the

crowded thoroughfares leading to the docks, in the lodging houses kept by East

Indians, in the shops frequented by Arabs, Indians, and Chinese, and in the

spirit houses and opium smoking rooms that one meets the most singular and most

picturesque types of Eastern humanity, and the most striking scenes of Oriental

life.”

The locals, however, were not so enamoured of these ‘foreign elements’ in their midst. By 1861

there had begun to be complaints about “an increase of low lodging houses

for sailors… and the removal of the more respectable families to other

localities.”

But not everybody

was hostile - many social reformers and religious organisations saw Limehouse

as a source of concern. It was observed how lascars that awaited their return

passages in London, were ill-treated, impoverished and neglected. Often men

jumped ship, choosing to starve on the streets rather than be subjected to the

hellish conditions on board ship. Others were abandoned by their employers when

they landed at port, either because they were not needed or because of

opposition from white seamen.

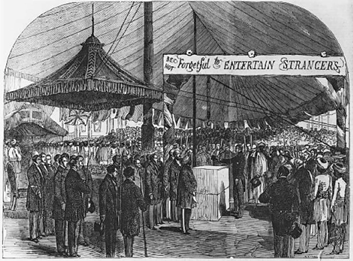

missionary societies who mostly wanted to provide a more wholesome alternative to other ‘low’ lodgings in the area. The largest and most famous organisation that responded to these issues was the Stranger’s Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders’ which opened in 1857 on West India Dock Road. There was also the Sailor’s Palace at 680 Commercial Road, a hostel run by the British and Foreign Sailors’ Society, built in 1901 and financed by the philanthropist Passmore Edwards. Other institutions sprang up to meet a clear demand.

The numbers of foreign sailors continued to grow during the 19th century and a large influx of Chinese workers, arriving from the 1880s onwards, gave rise to yet more suspicion of ‘foreigners’. By the 1920s, Limehouse was universally known as the capital’s Chinatown and became infamous for its opium dens. What’s more, the locals’ negative attitudes were further bolstered by books such as Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series (Dr Fu Manchu was a diabolic character bent on world domination and destroying white civilization) which played up the issue of crime in the Chinese community. Fear of the ‘Yellow Peril’ was a real feature of the age. Thomas Cook even ran tours for ‘daring people’ wanting to gawp at strange, exotic foreigners!

To give an idea of

the size of the problem, by the end of WW1 16,000 seamen from all over the

world were being let loose in the city every night looking for lodgings. Only

three quarters of them would have any luck which meant “they were prey to all

temptations“, as the more scurrilous newspapers put it!

In the end, an appeal was started throughout the Empire, largely organised by women, (in particular the Ladies’ Guild of the British Sailors’ Society, headed by Beatrice, Lady Dimsdale) to raise the necessary money to build this hostel, which would also stand as a memorial to the 12,000 merchant sailors who were killed in service during the First World War.

When it opened in

1924 the hostel, known as the Empire Memorial Sailors’ Hostel, provided 205

clean and airy single ‘cabins’ and these were much in demand, with sailors

having to book in advance to guarantee a place. By 1929 the hostel had provided

beds for over a million sailors. As well as a cabin of your own you would also have

access to a large lounge, dining-hall, billiard room and a chapel. In the 1930s

a room would cost 1/6 a night or 8 shillings a week. Such was the success of

the Memorial Hostel that a second wing was built in 1932 round the corner on

Salmon Lane with 100 cabins and a large function room.

Despite taking on a whole new guise, the building’s earlier character is reflected in details such as maritime-themed carving and attractive detailing on the stairways etc.

Webpage: https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/chinese-limehouse-and-mr-ma-and-son

Webpage: https://tammytourguide.wordpress.com/2023/04/05/discovering-the-chinese-in-britain/