London’s

Gates

The gates into the city

of London have long since disappeared (all demolished 1760-1767) but their

names linger on in the names of streets and districts of the modern city.

The Romans built a fort

around 120 AD. Between 190 and 220 AD a defensive wall went up, made of Kentish

ragstone. This structure, 6 metres high and 3 metres thick, incorporated one of

the fort’s gates (Cripplegate) and created four new ones: Aldgate, Bishopsgate,

Ludgate and Newgate. Their function, unsurprisingly, was to control traffic in

and out of the city and allow for the collection of any tax due on goods being

transported. Aldersgate was added by the Romans around 200 years later. Moorgate

came along much later, in 1415.

|

Roman Londinium showing position of gates |

|

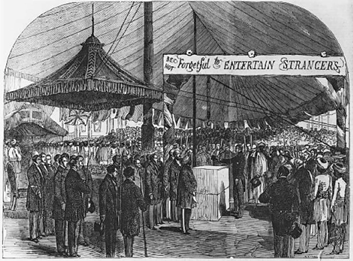

Engraving for Harrison's History of London 1775 |

|

| St Botolph's without Aldersgate |

Known in Saxon times as the Ealdgate (old gate), Aldgate is thought to pre-date the building of the Roman wall and spanned the road to Colchester, England's former capital. It was rebuilt in the early 12th century. The writer Geoffrey Chaucer lived in rooms above the gate from 1374 to 1385 when he worked as a customs official for the Port of London.

|

| Aldgate |

|

| Cripplegate |

The name Cripplegate is thought to derive from the old Saxon word crepel, meaning a narrow covered gate or passage. The body of Edmund the Martyr passing through in 1010 led to the belief that the gate had miraculous powers of healing. The gate was rebuilt in 1244 and 1491, and renovated in 1663.

Ludgate’s name is often

attributed to the early British King Lud, but is more likely to derive from

‘flood’ or ‘fleet’, due to its closeness to the Fleet river. It was the gate

which led to one of the main Roman burial mounds. Ludgate was rebuilt in 1215,

1586 and then repaired post-1666. When it was finally demolished, its statues

of Lud and Queen Elisabeth I (the only public statue ever made of her in

London) were removed and now stand outside St Dunstan’s Church in Fleet Street.

Moorgate takes its name from Moor Fields, a large piece of open land in the city. The gate allowed access to recreational activities there. The last of London’s gates to be constructed, it was originally a narrow postern gate unsuitable for heavy traffic. It was renovated in 1472, and then rebuilt in 1672 when the gate entrances were made higher to enable the elite regiments of the London Trained Bands to march through with pikes held aloft. On its demolition in 1762, stone from the Moorgate was used to strengthen London Bridge.

References:

https://barryoneoff.co.uk/the_gates.htm

https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/london-wall-and-gates/

https://livinglondonhistory.com/londons-ancient-roman-and-medieval-walls-a-self-guided-walk/

.jpg)

,_Piccadilly_Circus,_London_(2).jpg)