Postman’s Park

On a

walk around the city of London a couple of years ago, I happened across this

unexpected little hideaway near the city, known as Postman’s Park. Situated in

what was once the churchyard of St Botolph-Without-Aldersgate, not far from St

Paul’s, the park gets its name from its popularity as a lunchtime haunt for

workers from the old General Post Office building in nearby Newgate Street. It

is also home to a unique memorial – well worth a visit if you’re ever passing

by… and guaranteed to have you sobbing into your sandwiches in no time!

The monument was the brainchild of the

Victorian painter and sculptor G.F. Watts. A social radical who twice refused a

baronetcy and made no attempt to disguise his contempt for the upper classes,

Watts was a great believer in art as a force for social good. He first

conceived the idea of a national memorial to “heroes of everyday life” in 1887 as

a worthy way to mark Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The first site proposed for

it was Hyde Park, but this was rejected in favour of a small green space which

had been laid out in 1880 on the site of the former churchyard and burial

ground of the church of St Botolph-Without-Aldersgate.

The monument was the brainchild of the

Victorian painter and sculptor G.F. Watts. A social radical who twice refused a

baronetcy and made no attempt to disguise his contempt for the upper classes,

Watts was a great believer in art as a force for social good. He first

conceived the idea of a national memorial to “heroes of everyday life” in 1887 as

a worthy way to mark Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The first site proposed for

it was Hyde Park, but this was rejected in favour of a small green space which

had been laid out in 1880 on the site of the former churchyard and burial

ground of the church of St Botolph-Without-Aldersgate.

The monument was not finally dedicated until

1900. At the unveiling, a

short service was held in St Botolph's, after which a speech was given by the

Bishop of London in which he observed that: “It was a good thing that the multitude who took their recreation in

this open space should have some great thoughts on which to fix their hearts,

some inscriptions before their eyes recalling to them the things which had been

done by those who did their duty bravely, simply and straightforwardly in the

place where God had placed them. Such were, indeed, the salt of the earth, and

it was by producing characters such as theirs that a nation waxed strong.” Watts,

by now 83, was too ill to attend the ceremony and was represented by his wife.

The memorial takes the form of a 50ft-long wooden loggia built onto a wall, with seating below. It was initially planned to have the inscriptions engraved onto the wall, but then hand-painted,

ceramic wall tablets were chosen instead. Watts had it built with space for 120 tiles in five rowstoday two of those rows are still empty. The tiles in the middle row were made by the ceramicist William de Morgan, the top and bottom rows by the Royal Doulton factory in Lambeth.

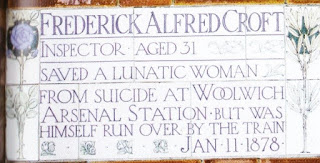

The plaques commemorate acts of heroism

carried out by ordinary Londoners – men, women and children – whose ages ranged

from the eight year-old Henry Bristow to Daniel Pemberton, who met his end at

sixty-one. Watts collected hundreds of newspaper cuttings of heroic acts, from

which the most “astonishing” were chosen for the memorial. The people

commemorated on the first thirteen plaques were chosen by Watts himself. After

his death, his widow added a further forty – with floral decoration and blue

lettering – and a small statuette of Watts in the centre.

The plaques commemorate acts of heroism

carried out by ordinary Londoners – men, women and children – whose ages ranged

from the eight year-old Henry Bristow to Daniel Pemberton, who met his end at

sixty-one. Watts collected hundreds of newspaper cuttings of heroic acts, from

which the most “astonishing” were chosen for the memorial. The people

commemorated on the first thirteen plaques were chosen by Watts himself. After

his death, his widow added a further forty – with floral decoration and blue

lettering – and a small statuette of Watts in the centre.

The memorial takes the form of a 50ft-long wooden loggia built onto a wall, with seating below. It was initially planned to have the inscriptions engraved onto the wall, but then hand-painted,

ceramic wall tablets were chosen instead. Watts had it built with space for 120 tiles in five rowstoday two of those rows are still empty. The tiles in the middle row were made by the ceramicist William de Morgan, the top and bottom rows by the Royal Doulton factory in Lambeth.

The plaques commemorate acts of heroism

carried out by ordinary Londoners – men, women and children – whose ages ranged

from the eight year-old Henry Bristow to Daniel Pemberton, who met his end at

sixty-one. Watts collected hundreds of newspaper cuttings of heroic acts, from

which the most “astonishing” were chosen for the memorial. The people

commemorated on the first thirteen plaques were chosen by Watts himself. After

his death, his widow added a further forty – with floral decoration and blue

lettering – and a small statuette of Watts in the centre.

The plaques commemorate acts of heroism

carried out by ordinary Londoners – men, women and children – whose ages ranged

from the eight year-old Henry Bristow to Daniel Pemberton, who met his end at

sixty-one. Watts collected hundreds of newspaper cuttings of heroic acts, from

which the most “astonishing” were chosen for the memorial. The people

commemorated on the first thirteen plaques were chosen by Watts himself. After

his death, his widow added a further forty – with floral decoration and blue

lettering – and a small statuette of Watts in the centre.

Despite the melodramatic tone of their

language, the stories the tiles tell are moving. The earliest of the tablets

commemorates Sarah Smith, “a Pantomime

Artiste at Prince’s Theatre, who died of horrible injuries received when

attempting in her inflammable dress to extinguish the flames which had

enveloped her companion. January 24th 1863.”

The plaques honouring children are

particularly poignant. They include: “Solomon

Galaman: Aged 11, died of injuries September 6, 1901 after saving his little

brother from being run over in Commercial Street : ’Mother, I saved him but I

could not save myself’”, “Alice Ayres: daughter of a bricklayer’s labourer, who

by intrepid conduct saved three children from a burning house at the cost of

her own young life” and “Harry Sisley of Kilburn, who was just ten when in 1878

he drowned trying to rescue his baby brother.”

After her

husband’s death in 1904, Mary Watts lived for another 34 years, and was buried

alongside her husband in Compton. Following her death, the memorial was

abandoned half-finished, with only 52 of the intended 120 spaces

filled.

In June, 2009, the first new plaque for over

seventy years was unveiled in the park. However, it is unlikely that more will be added. The Friends of the

Watts Memorial, who oversee its care, have made it clear they do not want the

historical integrity of this unique memorial to be compromised by the addition

of more tiles. The memorial is now Grade II listed.

St Botolph's

remains open as a functioning church, but because of its location in a now mainly commercial area with few local

residents, services are held (unusual in this country) on Tuesdays instead of the more traditional

Sundays.

111 Places in London That You Shouldn’t Miss John Sykes (2016)

Website: http://www.wattsmemorial.org.uk/

Website: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postman's_Park

References:

Tunnels,

Towers & Temples: London’s 100 Strangest Places David Long (2007)111 Places in London That You Shouldn’t Miss John Sykes (2016)

Website: http://www.wattsmemorial.org.uk/

Website: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postman's_Park